Commentaries on the images

Ferdinand E. Hart Nibbrig neither commented on his images, nor accompanied them with theoretical reflections. He omitted any titles as he regarded them as ‘viewing crutches’ and ‘false paths’. The images – ‘eye matters’ – should speak for themselves. Only when work came to a halt would he explain this through a temporary lack of dynamic equilibrium of two opposing tendencies, graphic solidification and pictorial liquefaction in favour of transparency. Thus the switch from oil to watercolours and finally to acrylic becomes explicable. He said that the quick drying of this medium forced him repeatedly to set the process of painting in motion and keep it going. The following texts of three different onlookers are potential suggestions of an inquiring, open- ended image reading:

-

-

...the border town of Basle during the Second World War – the blazing sky seems to speak of it; not to be overlooked: the three colours dominating the painting can be found again in the flag of the ship anchoring on the shores of the river Rhine. It is Europe’s oldest Tricolour, that of the Netherlands, now occupied by Nazi-Germany, homeland of the painter from which he has been cut off for political reasons... C.L.H.N.

-

-

They sit with crossed limbs lined up next to each other like letters of a bulky, not yet deciphered brushwork. They offer something to read. Perhaps they are called ‘disappointed souls’ or ‘life weary’ and came here from Hodler? Were they freed from his atelier and pathos and retranslated with nonchalant zest into the village café?

And the colours – do they come from Arles and know of van Gogh’s yellow ochre and midnight blue?

The one with the cap is still awake holding the unfolded white newspaper, deeply absorbed in what’s printed, which is hidden from our sight. The news might be unpleasant; after all we are in the 30s.

The door in the wall is open. The one squatting looks into brown heaps. The window has been closed crosswise, as if by a child’s hand, a primitive sign of mystery and promised safety.

Beneath the line, like a signature: The dog on his trail. The ticker tape of life.

En route into the future? Perhaps into Giacometti’s atelier. AS

-

-

The summer of 1947 was exceptionally hot. That’s on record. The fields are glowing. Only the clouds are clad in white and would like to wander.

Meanwhile family life below rests baffled at the garden fence and everything ebbs away in its nowhere land.

Even the painter is lazy. Before he drops his brush he holds onto the green-green of the freshly painted garden table.

Clownish structure, bravely maintaining a vague geometry. Something needs to keep shape when the land vibrates, to be ready for the evening, when it will get cooler and people will gather at the appointed hour. AS

-

-

At first all was snow. While it was still night, a grove grew on the hillside. Crows gathered there. They dreamed of the light. It grew foggy and yellow on three spots. Star. House. Child. First the star, then the house, flickering cheekily in its hideout, finally the child. Round and present, covered in yellow. It did not come a way, it is already in the foreground, probably there for ever. On the threshold to us on the outside, who are learning how to see. AS

-

-

...domineering eye catcher in the nocturnal background: the memory of the Piz Uccello in the Mesocco valley, the strangely lit after-glow; painted ‘par coeur’, as the painter termed his method. As if the cows instinctively understood the pale radiation of the recently risen full moon as an urge to run together forward and downward out of the picture, into the intervening space of the encounter between the picture and the viewer, who is also in this case, as so often, invited to engage in the transitions between different levels of consciousness and reality... C.L.H.N.

-

-

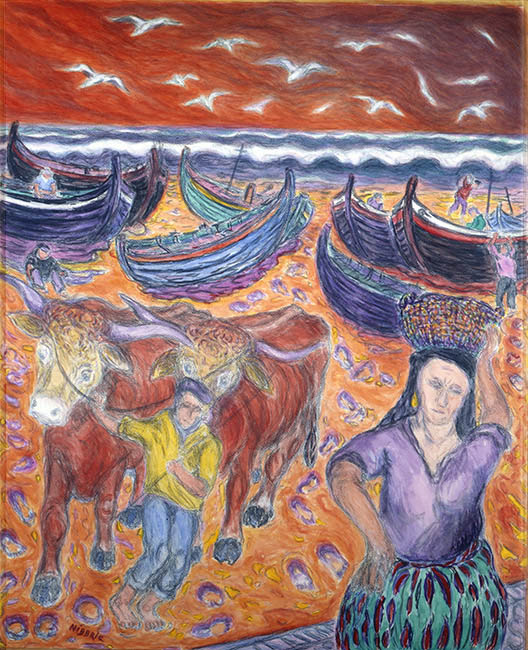

To observe everyday scenes, to be mesmerised by the daily trade of simple folk, be they Portuguese fishers, farmers or artisans in the Netherlands, as was Jozef Israel, in whose atelier in the Jewish quarter father worked at the beginning of his time in Amsterdam. Pictures by Max Liebermann painted in Laren: The Flax Barn, Walking to Church. Perhaps young Hart Nibbrig knew them from reproductions, also his Cobbler’s Workshop or the Sewing School and the etchings of the Jewish Market in Amsterdam. AM

-

-

A picture full of different velocity movement. A peasant couple homeward bound on their bicycles, four turtle doves on the wayside billing and cooing, an elderly women pushing her vegetable cart, swifts circling around the church tower in the evening light, shortly before heading south. Composed in minute detail are the paving, the cemetery wall, the surface of the church roof, the glowing evening sky, the stained glass church windows. AM

-

-

... as if colour pre-existed form: the grazing red horse seems to body forth from the pigment of the piled up towering red clouds; a white one next to it, wondering bemusedly, gazing forward into the optically cropped image space; and in the foreground, amidst blossoming and withering flowers, the same horse once more:. its placeholder in the foreground? A dreamt horse in a horse’s dream? All ears, all eyes. Is it still an animal? At least a living being that shares its aliveness with man in such opening awareness. In a secret alliance of colour with the white waving wisps of clouds in the sky behind and thus mysteriously affirmed by this. An image within the image, hovering bodiless and enigmatically magnified in front of the rest of the picture, painted differently, in the medium of another, second-grade reality. Omitted in a dematerializing way, as if the canvas would filter through as the painting support in the delicately nuanced opaque white of the pale moonlight, protruding from the picture into another dimension, towards the onlooker, who being heard and seen in such a way, has always been in the painting, not simply in front or opposite to it. And, who knows, the painted creature might expect to wake up in the onlooker’s eyes, which read the dream image from back to front and back again, not from, but in its dreaming, and thus the image would finally reach itself. The radiating yellow sun of flowers in the structural centre of the picture celebrates anticipating the small eternity of that blink of the eye... C.L.H.N.

-

-

... recognizable: the church of Oltingen in the Sundgau in Alsace, this time in a provocative sparkling red, which undercoats the precipitously erupting unstoppable savagery in this enchanted and tranquil winter painting, manifested in the wild boars that frantically cross the reddish field in the foreground. This is realized in the chasing drift of the clouds – wisps of snow in a darkened sky above, in the opposite direction – concentrated and transformed into a landscape of the soul. Thus the picture keeps a trembling balance between silence and a hidden unrest…C.L.H.N.

-

-

... the artist himself called his late still lifes nature morte et vivante: pictorial meditations on vitality in connection with opposing force fields, such as liquefaction and hardening crystallisation, centrifugal and centripetal... C.L.H.N.

-

-

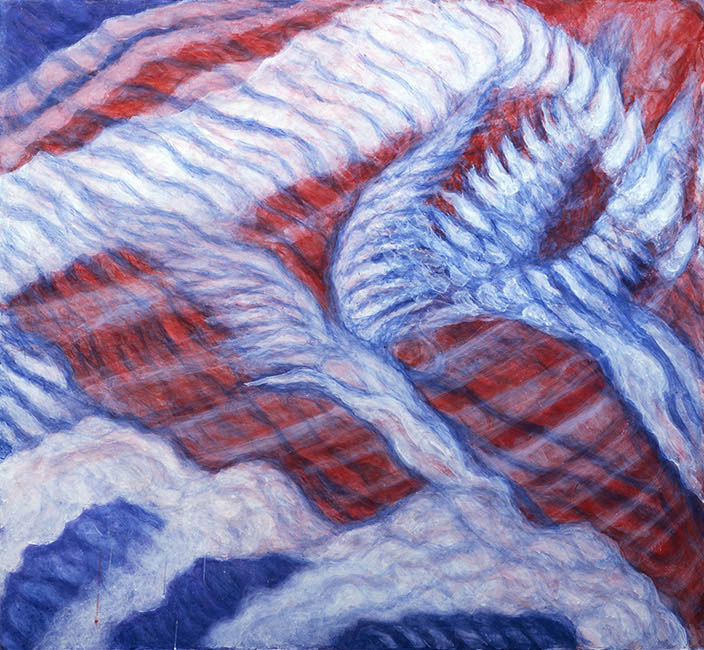

‘Waving wings’. The basis of this picture is the natural observation of feathers fusing into the form of waves and leading to abstraction. Nature becomes an autonomous art world with its own legitimacy through the creative hand. The preference for red-blue-white as an allusion to the origins of the very distant past? AM

-

-

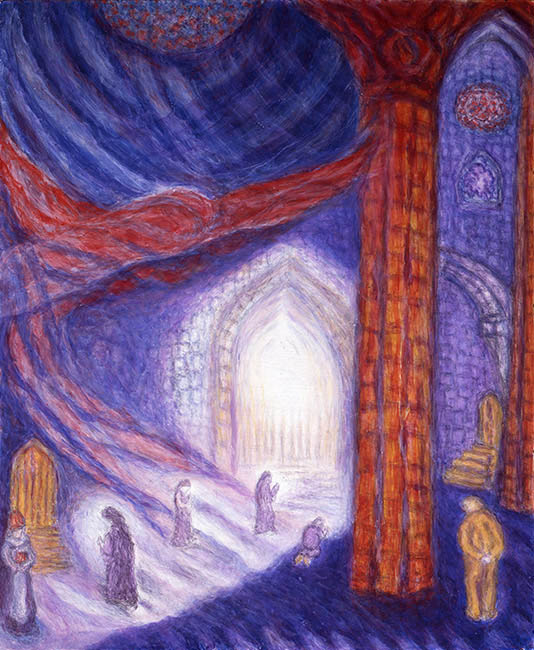

The gate between the mightily rising pillars of the gothic architecture leads to an unknown brightness. Angelically shadowed people wait in prayer in the theatrically illuminated interior. Worked out in the resistance of acrylic paint instead of elegantly diffluent watercolours. The adumbrated area that welcomes our curious gaze is full of cautious assuredness. The motif has developed over decades between the poles of knowledge and intuition. It remained unfinished as the final painting on his easel. AM